Let’s take the confusion out of strategy and sail across the ocean

(When I meet with business executives, I usually ask “what’s your strategy for growth?” At a trade show I attended a few weeks ago, that question was often met with silence or a list of tactical programs that had no overall direction other than selling. I wrote a similar blog post to this years ago and received a lot of positive comments so I thought the time is right to bring it out again.)

Strategy isn’t a tangible program like an event or an ad, so it’s easily misunderstood and its importance is diminished. Our business culture values action. “I need someone who can hit the ground running”, is a common refrain from managers who believe action is what creates results. But the real question is “what direction are you running?” Action without direction is meaningless or even harmful and I keep hearing confusion about why strategy is important and how objectives, strategy, tactics and goals are related.

It’s simple enough to say that “objectives are measurable, strategy is direction, and tactics are actions.” But the question still asked is: “How many strategies should we have?” Well, if strategy is direction, how many directions can you go at the same time? No wonder we’ve become accustomed to business plans underperforming and confusion reigning among both employees and customers. Marketing departments and their agencies often don’t know what direction they’re going or they create separate strategies for each tactical execution. Consequently, tactical programs may have no clear direction or consistent message and the result is that they get lost in the competitive clutter.

I grew up learning to sail and race sailboats in small lakes and across the ocean and I can think of no better learning tool for understanding objectives, strategy and tactics, and removing the confusion around them.

Building a business is like crossing the ocean

Suppose, we decide to sail a boat across the Atlantic Ocean. This isn’t something most of us will ever do but objectives, strategy, tactics, and goals as well as research, even management teams, become crystal clear when setting out to cross the ocean and they’re no different than they are in business.

For fantasy purposes, we can become part of the idle rich and plan to sail our boat from the Chesapeake Bay area to the mouth of the Mediterranean in late June. Why not? The Mediterranean is a nice place to spend the summer. Since we’re in a hurry to get there in time for party season, we’ll set an objective of reaching the Mediterranean in 20 days. So now, we’ve set an objective and it’s measurable. We can break it down further to measure our progress along the way. It’s about 3,800 miles in a straight line across, which means we’ll have to average about 190 miles every 24 hours. That will require an average speed of 7 nautical knots per hour (a little more than 8 miles per hour). That may sound slow but we’re dependent on the vagaries of the wind and weather conditions as we sail across. More importantly, we now have a set of metrics by which we can measure our progress, a key component of objectives.

To take our fantasy voyage further, we’ll need a boat and considering our objective, we might want one that’s about 60 feet long, something like the one in the photo above. This boat is called a Swan 60 and is made by Nautor in Finland. Nautor makes safe, fast and beautiful boats and we’ll pay a pretty penny for the privilege of owning one. Fully equipped, we’re looking at around $3.5 million but hey, it’s only money! The good news is that the Swan 60 has what’s called a hull speed of about 10 knots (approx. 11.5 mph). Without going into a technical definition, hull speed is the approximate maximum speed a boat can go. The exception to hull speed is when a boat surfs in high winds on top of the waves. If we can get our Swan 60 surfing, we can probably sail at speeds well over 15 knots. So averaging 7 knots across a 3,800 mile span of ocean does not seem out of the question.

Now we have our boat and you can think of it the same way as we might a business. It has an owner (a wealthy one) who may or may not be “skipper” (no jokes please) or managing director. We’ll need a navigator, who can be compared to a combination of a Chief Technical Officer and Chief Strategy Officer, and a Tactician, our Chief Operating Officer to keep us going at maximum speed. Then we’ll need some specialists, people who excel in working in different areas of the boat and handling a 60-foot yacht’s large sails. Also, we’ll need an experienced sailboat cook who knows how to keep a crew happy while being tossed around in large waves. We’ll want experience all around as ocean sailing is not for novices. In all, our team may total 14 people. Our boat only sleeps seven but we’re sailing non-stop 24/7 so we’ll need enough people to manage the boat while others sleep.

Selecting a strategy

You can see by now that we’re building a small company that has an ambitious objective. Now, it’s time to select a strategy, a direction we’ll take to reach the Mediterranean on time. We have some difficult choices to make. It’s time to do some research.

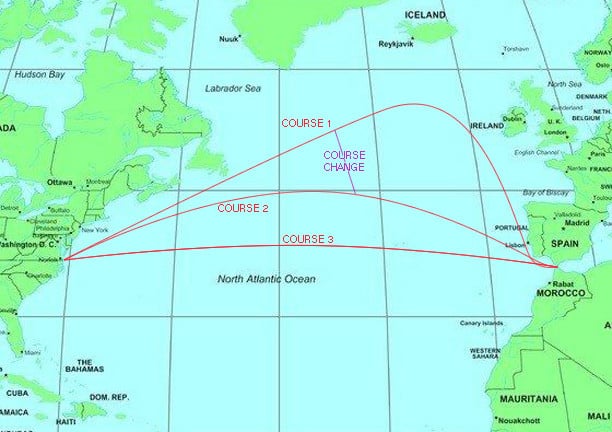

We’ll study historical weather patterns, learn the prevailing winds, ocean currents, note the islands or hazards we might see along the way and course taken by other boats making the same crossing. We learn that there are three optional courses across, each with its strengths and weaknesses. We can devise a SWOT analysis (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats) for each of them. The map below shows our choices.

Course 1: High-risk; High-reward

This is a strategy that has some clear risks but also enticing opportunities. It takes us northeast along the U.S. and Canadian coastlines. As the prevailing summer winds are out of the southwest, we’ll be sailing downwind, which should give us more speed. We’ll also be assisted by the Gulfstream currents, which run along a path from the Bahamas northeast into the Atlantic at an average rate of 3 knots. Then, if weather patterns hold, we should have good winds reaching down the European coast to get to our destination. The risk is that we’ve added about 1,000 miles to our course, which means we need to average 9 knots, which is pretty aggressive. Another risk, more precisely, a threat, is the possibility of sailing among drifting icebergs, once we’re off the Labrador coast. Our research has told us that iceberg fields breaking off from the Greenland glaciers are common during the summer months. That’s not a problem for us during good weather but it’s difficult to see an iceberg at night (memories of the Titanic). So in the end, we have a potentially fast crossing to meet or exceed our objective but with some significant risks.

Course 2: Shortest Distance

This is a strategy that takes the shortest possible course using the curvature of the earth to shorten our path. It still has the potential risk of icebergs but it is more manageable if this becomes a problem. We’ll gain less of a push from the Gulfstream and may find ourselves stuck with low or no wind for days in a mid-Atlantic high-pressure system, but it seems to strike a middle ground that still makes our objective within reach.

Course 3: Nice & Easy

This strategy is the most conservative. It enables us to stop along the way in both Bermuda and the Azores, letting us replenish our supplies 700 miles east of the U.S. and about 1,000 miles west of the Mediterranean, with a gap of about 2,000 miles in between. This course reduces the risk of being exposed to extreme weather along the way and allows us to spend a night or two in safe harbors on our course. The risk is that high-pressure centers regularly sit in the middle of the ocean in late June and we could have to drift windless or move at low speeds for days. This may make it difficult to reach our objective on time. (BTW, this course appears shorter when viewed as a flat surface but is longer when going around the diameter of a sphere.)

Our three strategies are not too different from what we may see in business, one that is high-risk, high-reward, one that is safe but potentially slow and one that is a middle ground or compromise between the two. Which should we choose and what happens if we recognize that we’ve made a mistake?

Suppose we’re aggressive and have tremendous confidence in our abilities to manage the boat and navigate the seas. Past success might even blind us to some of our weaknesses. When hubris takes over, decision-making can be reckless (memories again of the Titanic…or hundreds of failed businesses). Let’s assume we select the high-risk course that takes us far north but in doing so, we find the hazards of icebergs to be too many, the seas to be too rough or even the winds to be less than we anticipated. As a result, we decide to change strategies and move mid-course to another direction. One look at the “course change” on the map shows the cost of making this correction, which is likely to make our objective much more difficult to reach. The lesson, of course, is that selecting the wrong strategy and making a change has costs, which can be significant.

Tactics and goals

What about tactics and goals? How do they factor in and how should we think of them. During any period of time, we’re going to take specific actions to increase the speed of our boat. We might put up different sails, larger or smaller, to take advantage of changing winds. Or, we might want to be on a slightly more advantageous course to gain speed. These are tactics but are not strategy, as they don’t alter our overall direction in reaching our objective.

Imagine a boat (or a business or someone who hits the ground running) that is all tactics but has no strategy. It would always take every possible action to increase its speed regardless of the direction it is heading. It might even go in circles and get nowhere very fast. Tactics will not reach a productive objective without strategy to provide guidance.

Finally, where do goals fit in? Goals are long-term milestones that you want to achieve. (e.g. “I want to be a better sailor/manager/person.”). Objectives are fixed and have specific requirements, which can be measured. Objectives have structure; goals do not. Goals can never be accomplished without objectives but objectives without goals won’t create the long-term change you desire.

Hopefully, that clarifies things. Following college, I crewed on a large sailboat crossing the Atlantic. Our owner chose “Course 3: Nice & Easy” and we paid a price for it. It was slow, slow, slow – 27 days across. But one of my strongest memories of that trip was listening to our marine radio and hearing reports of sailboats dodging icebergs in high winds only a thousand miles to our north. It was an example of how the wrong strategy can have its costs, either going too slow or too fast, but it cemented the concepts in my mind forever.

(A clear understanding of strategy also requires tools that help clarify its risks and rewards and tell which tactics make the most sense in any given direction. Gaining a clear understanding is the principle behind Oomiji so you can select the best direction and tactics that help you reach your objective faster.)